The coronavirus as seen by a social psychologist. What’s going on in people’s heads?

When uncertainty really makes itself felt, some people try to fight it by focusing on conspiracy theories. “A sense of losing control, frequently fed by the media or by political sniping, can in extreme cases have even more severe effects than the virus,” writes Dr. Marta Marchlewska from the PAS Institute of Psychology. Read her article to find out more.

The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is causing growing fears in countries all over the world. The chief of the World Health Organization has announced a global pandemic, while the media are posting minute-by-minute updates on the number of infections. The Polish government has ordered closures of nurseries, kindergartens, schools and universities, as well as theatres, cinemas, operas and other cultural sites. The authorities are also imposing limits on public gatherings. So what’s going through our heads while all this is going on?

Regaining a sense of security

The current sense of psychological threat means we are trying to take back control over the situation. This can be done in many ways: by obsessing about hygiene, hoarding supplies, paying even closer attention to one’s own or others’ health, and so on.

A sense of uncertainty surrounding the coronavirus pandemic also seems to lead to destructive phenomena, all too familiar to social and political psychologists. Examples? The internet is overwhelmed by information chaos and a plague of fake news. Conspiracy theories abound, insinuating alternative explanations for the roots of the epidemic. Why is the virus spreading so fast? Is someone hiding a cure for the coronavirus? Are we being kept informed about the real situation in the country? There is plenty of speculation online on these and other topics. Although the rumors are rarely supported by any evidence, they carry a massive emotional load and frequently lead people to seek out groups to blame for the current situation.

Who reaches for conspiracy theories?

Studies I have conducted with Prof. Małgorzata Kossowska (Jagiellonian University) and Dr. Aleksandra Cichocka (University of Kent) in 2018 reveal that people with a high desire for cognitive closure (or a low tolerance for ambiguity) are especially susceptible to conspiracy theories at times of uncertainty.

In other words, when uncertainty becomes very uncomfortable, some people try to eliminate or at least reduce it by putting faith in conspiracy theories which provide clear (although not necessarily accurate) answers to difficult questions. Such ideas tend to accuse specific groups of people of secretly running the world and attacking the individual’s own community. Such individuals try to cope with uncertainty and stress by focusing on supposed perpetrators of negative events and directing anger towards them. In practice, this frequently leads to discrimination of certain groups and diverting attention from the problem at hand.

Collective narcissism

Our other projects (also conducted in partnership with the Political Psychology Lab at the University of Kent) show that a sense of losing control is a driver of defensive group identification (collective narcissism). This carries negative consequences, both on group (such as hostility to strangers) and individual levels (negative emotions and a lower sense of wellbeing, as shown by research conducted by the team led by Prof. Agnieszka Golec de Zavala from Goldsmiths, University of London).

The results of our research show unequivocally that secure group identification – which makes people want to be constructive and engage in efforts for the common group – is founded in a high degree of control, rather than uncertainty or even panic.

Fighting the coronavirus by closely following the recommendations of the World Health Organization is essential at this time, but we must not forget about the psychological impact of the pandemic. The sense of losing control, frequently fed by the media or by political sniping, can in extreme cases have even more severe effects than the virus.

About the author

Dr. Marta Marchlewska works at the PAS Institute of Psychology where she leads the Political Cognition Lab. She works in social and political psychology, and she specializes in quantitative data analysis and psychometry.

Dr. Marchlewska’s projects focus on the function played by various kinds of psychological threat in our perception of the political world. She is particularly interested in personality variables such as self-esteem, narcissism and ways of identifying with groups, and she links them with political preferences such as support for democracy, populism and belief in conspiracy theories about the political world.

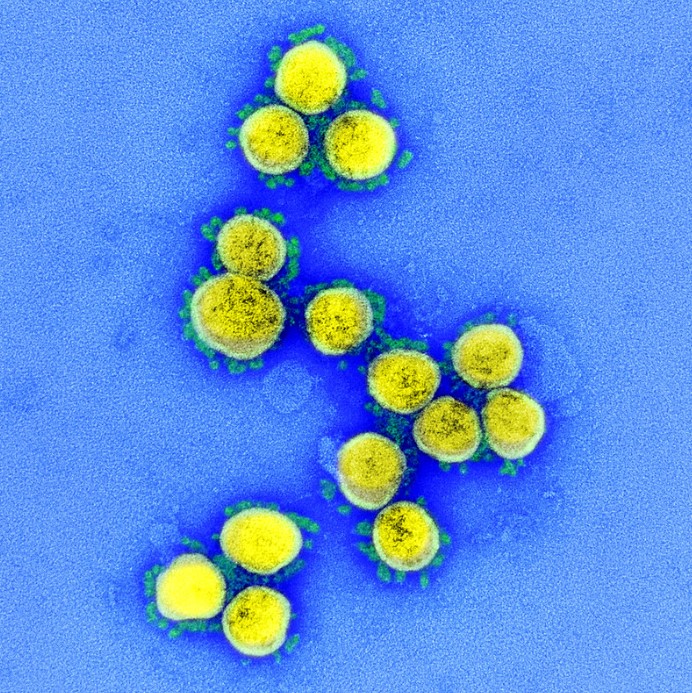

Pictured: The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus viewed by an electron microscope. Source: NIAID / CC BY 2.0